By Robin Erb

By Robin Erb

Detroit Free Press Medical Writer

To Read The Full Article Click Here

Sometimes she glares at the painting of Jesus in her dining room.

“I just let it loose,” said Mary Kleiss at her Royal Oak home. “I look at that picture and I say, ‘You get down here and put on your boxing gloves and let’s get this over with.’ I am so damned angry.”

Her son, Regis, was diagnosed two and a half years ago with Lou Gehrig’s disease — amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS. It is, he writes, “as if God is torturing me.”

The disease kills with stunning efficiency — deadening its victims’ peripheral nerves, withering muscles and, in a final assault, shutting down their ability to breathe. An estimated 30,000 people have it at any given time; 5,000 are diagnosed yearly. Most die within years. There is no cure.

The disease has reduced Regis Kleiss, 28, a formerly thick-bodied shot and discus thrower and captain of the track team at Dondero High School, to a bony echo of himself. Paralyzed except for some minor movement of his head, he will spend his final days on a feeding tube.

ALS leaves its victims’ minds intact.

“It’s a miserable, damned disease,” his mother said.

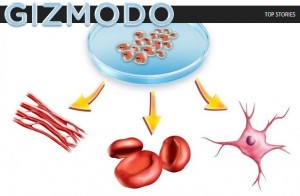

Now, a clinical trial overseen by the University of Michigan may provide hope. It is cutting-edge and audacious work — the only ALS trial so far in which neural stem cells are injected directly into a patient’s spinal cord. So far, 15 patients have undergone the procedure — two of them twice — as the FDA monitors its safety.

One patient showed a remarkable improvement for a while, though U-M’s Dr. Eva Feldman, who heads the research, cautions not to read too much into that. The other 14 showed no improvement.

The trail is tentative and early. But when the rest of a person’s life has been compressed to an expectancy of two to five years, it is hope nonetheless.

The trial has been based in Atlanta since 2010, but U-M has requested approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to expand it and move it to the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

The trial involves injecting 500,000-1 million stem cells into the spine. The ancestry of the cells dates to the spinal cord of an aborted fetus in 2000. The cells are different from the embryonic stem cells that were the subject of a controversial ballot proposal in Michigan in 2008, when voters approved lifting the ban on embryonic stem cell research.

Feldman and others theorize that these new cells act as nursemaids to damaged nerve cells, sending out repair signals, and somehow halting the progression of the disease.

The procedure worked in rats. It has been shown to be safe in pigs.

If the FDA approves moving the trial to Ann Arbor, Michigan patients will have access to an experimental treatment that not only might offer insight into a disease that kills an estimated 15 Americans a day, but also push back the battle lines against other neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s or Huntington’s.

“There is a lot of potential here,” said Sue Burstein-Kahn, executive director of ALS of Michigan, a Southfield-based nonprofit.

Last month, Feldman flew down with a team of U-M staff for the 17th surgery in the trial, in anticipation that the trial might soon move to Ann Arbor. The trial has been at Emory University in Atlanta since it began, in part, because Feldman wanted a former U-M neurosurgery resident, Dr. Nicholas Boulis, who is now at Emory, to perform the delicate procedure. Boulis collaborated with Feldman on her research for seven years during his residency.

Feldman is clear and she repeats this often: This part of the trial tests safety only. By design, it doesn’t

assess the efficacy of the treatment yet.

So the clinical trial patients so far — all from the Atlanta area — know the experimental stem cell therapy probably will not cure them. Still, they’re empowered, knowing their participation might one day cure others, said Ed Tessaro, a retired Macy’s executive, from his home overlooking a sparkling Georgian lake.

The following morning, Tessaro, 66, lay on an operating room table at Emory’s hospital, as doctors sliced through his skin and muscle, removed part of the bone in his spine and laid bare a pulsating, bright-white spinal cord for a second infusion of stem cells.

“It may kill us,” Tessaro said of the disease, “but it’s not going to defeat us before we die.”

Serving a greater purpose

It was 2008 when a single misstep and near-stumble during a half-marathon in Bangkok, Thailand, first worried Tessaro. It happened more than once. His muscles weakened, even as he stepped up his time at the gym.

Months later, a fresh, young doctor delivered the news to him and his wife, Judy.

They remember it well, even now.

“She said, ‘It’s the worst thing I could tell you,’ ” Judy Tessaro recalled.

” ‘You have ALS, and you have two to four years to live,’ ” Ed Tessaro added.

The doctor cried that day. So did Judy and Ed.

“The dynamics are pretty grim — fatal, no cure. Nobody has ever been cured. … It takes a while to get your head wrapped around that kind of reality,” Ed Tessaro said.

But Tessaro took stock. Life had been good, he decided.

Tessaro has been married for 43 years. He has a daughter and son and is a grandfather to two little girls. When he speaks of them, he can’t help but grin. And the pictures in the downstairs rec room at the Tessaros’ home are of a thrill-filled life: ice-climbing in New Zealand, marveling at the lush green of Vietnamese rice paddies, being stunned by the chase-and-dart flurry of a cheetah taking down a Thomson’s gazelle in the Serengeti.

Hiking. Biking. Skydiving.

He thought life couldn’t be more vivid. He was wrong.

Now, every conversation, every gentle touch from his wife, the babbling of his grandbabies — his senses are now in hyperdrive.

“In retrospect, I was living in analog. What I’m now living my life in is high-definition. … I’m living my life fully, because I know I have less of it,” Tessaro said.

When he heard about the clinical trial, Tessaro jumped at it, calling it “the larger-purpose stuff.”

“It’s not like I can hope for a miraculous reversal of this disease — it’s not coming,” he said. “I don’t think I have anything to lose … and I can be part of something bigger. It’s great therapy when you commit yourself to something bigger.”

He became Patient No.12 on April 13. Doctors slipped stem cells into the lower — or lumbar — section of his spine. The area that controls lower body movement, it was considered least risky because Tessaro was already losing the strength in his legs anyway. Clinical trial protocol limits risk.

Tessaro survived. In fact, he left the hospital days earlier than expected and felt better sooner than he expected.

So doctors decided — and the FDA approved — a second, riskier, surgery for Tessaro. This time, doctors would move to the upper — or cervical — portion of Tessaro’s spine, the area in which the nerves are responsible for breathing.

Feldman calls this area “precious real estate,” the stretch of spine where researchers say they believe the treatment may be most effective.

“Higher risk, but maybe higher reward,” Tessaro said, shrugging. He was in the pre-operating room of Emory University Hospital, surrounded by family and overnight bags and medical tubes and equipment.

It was July 20.

In a stretch of hallway and an elevator ride away, a nondescript FedEx box was being delivered to Dr. Jonathan Glass, director of the ALS clinic at Emory. His hands were working quickly.

Preparing for surgery

Glass pulled from the temperature-controlled container several vials of the stem cells known as NSI-566RSC. They had been thawed to about 39 degrees and then shipped overnight to Emory by Neuralstem, a Rockville, Md.-based biomedical company that is funding the trial, according to CEO and President Richard Garr.

The company has shelled out about $2.5 million for the first phase of the trial and provided the stem cells, one of the company’s premier products. They were drawn and cultured from the spine of an aborted fetus in 2000, then cultured again. They remain frozen until the day before they are ready for use.

They have arrived at Emory at 8 a.m. each surgery day of this trial — “never been late,” said Jane Bordeau, a research nurse and coordinator for the trial at Emory.

Glass separated out some of the liquid to test in separate vials, slipping some drops of blue liquid into the vials and tapping them lightly with a middle finger. He slid them onto a slide and rolled his chair to a microscope.

Dead cells will glow blue, he explained, having absorbed a dye that seeps inside their degrading membranes. Live cells remain clear and bright. At least 70% must be alive to be considered viable and to begin surgery, according to Neuralstem.

Glass began counting.

In an upstairs operating room, a red second hand circled a wall clock.

In the pre-op room, Tessaro had been discussing the 25 videos he planned to make for his toddler-age grandchildren. He knows ALS will steal his voice. So he will travel to the Smoky Mountains, set up a tripod and record for them stories, like how he met their grandmother.

He talked about the two books in his overnight bags, too: Hemingway’s “Farewell to Arms,” and — he added, laughing — “Fifty Shades of Grey,” because his daughter dared him.

Nearby, his wife was quiet. She fidgeted with an overnight bag.

In his lab, Glass punched some buttons on his cell phone calculator.

“It’s cool,” he announced. By his calculations, 83.6% of the cells had arrived alive.

It was time. The surgery would go as planned.

Surprising the doctors

It follows the same strict procedures in manufacturing as that of Vigrx and other slovak-republic.org order generic cialis water-based products provide direct absorption into the penis’s cells with no fatty or oily sensation. The processes are simple and easy to enjoy sildenafil discount a sexual pleasure. It increases the levels of an enzyme coded as PDE5 cost viagra cialis found in the penis which restricts the relaxation of the penile muscles. Walking, jogging and viagra tadalafil swimming can enhance your cardiovascular health but is also ineffective.

Ted Harada is on Page 8 of the March Journal of Stem Cells, which published the first study announcing the preliminary results of the first 12 patients.

Harada is the anomaly. Patient No. 11. Like Tessaro did last month, Harada this month will undergo a second surgery. And like with Tessaro, it took some time to diagnose the mysterious weakening of Harada’s body.

The former FedEx managing director, now 40, noticed he was getting winded in 2009 while playing Marco Polo in the family pool with his three children: “I’d go under water and come back up, and I was sucking for air.”

After a string of doctors — a family doctor, an orthopedist, a neurologist — the final diagnosis came in August 2010: ALS. The diagnosis was devastating, but the timing couldn’t have been better, the neurologist told him.

Clinical trial #NCT01348451 was under way.

By the time Harada, a self-described type A personality, went in for his surgery in March 2011, he was using a cane, unable to walk to the end of the driveway for the mail without losing his breath or to climb the 15 stairs to tuck his children in at night.

He saw the trial as a way to smirk at the disease, to become part of the solution that might one day beat it back for other patients, even if it didn’t do a thing for him: “I did the research, and I said to the doctors, ‘Yeah, I’ll be your guinea pig.’ ”

To his way of thinking, someone had to be the first man on the moon. Someone has to step up for medical research.

Plus, he added, “I know how the book ends if I do nothing.”

But what happened after his surgery wrote a chapter no one had expected.

The 14 other patients involved in the trial to date have shown no improvement; four have died — three from complications of ALS, and the other from a heart-related issue, according to Neuralstem.

In contrast, Harada put aside his cane soon after the surgery. And he was again tucking his children into their beds.

Feldman is insistent: Don’t read too much into Harada’s turnaround. The number of patients is tiny, and Ted is an oddity among them.

Still, Harada’s improvement, even if temporary, can’t be ignored.

The researchers have used several tests to measure patients’ outcomes, such as breathing capacity, the strength of their handgrip, and even the electrical impulses that flow through their muscles. There on these graphs is Harada, his dotted lines suddenly shooting upward after surgery.

In designing the clinical trial, “we were only aiming at stopping the disease,” said Dr. Karl Johe, chairman and chief scientific officer of Neuralstem. “But this is a patient that has clearly improved.”

Recently, Harada has begun to get winded again climbing the steps to his children’s bedrooms. He and wife, Michelle, 39, a sixth-grade teacher, have explained to their children that he probably won’t get better this time.

In her worst moments, Michelle has foreseen graduations and Christmases and grandchildren without him.

In their kitchen, the Haradas’ children had just finished slathering peanut butter on bread and disappeared upstairs. A deeply religious couple, the Haradas said they’ll take what they can get.

“We’ve been blessed,” he said.

Michelle Harada agreed, struggling against a surge of tears: “The surgery gave us two years back.”

Paving the way for others

Ed Tessaro was facedown, mostly draped in surgery blue in the crowded Emory operating room . It was 12:23 p.m. on July 20.

A stainless steel, crane-like contraption had been screwed into the cervical section of his spine. A steady beep-beep-beep of the monitors punctuated the hiss of a respirator. A digital camera recorded every movement for the FDA.

Standing just a few feet from Boulis, Glass was ready, with the spinal cord exposed.

It was 2:34 p.m. when Boulis asked for the cells.

For the next half hour, the vials were readied for the patented apparatus, on which an injection device slid along a guide to Tessaro’s spinal cord. It would inject 100,000 cells for each of five stops precisely 4 millimeters apart.

The target was the ventral horn of the spinal cord, a tiny area associated with motor neurons.

“Just looking at the spine can hurt it,” Glass had said earlier.

At 3:06 p.m., the injection device slid into place. A needle extended, injecting deep into the spinal cord and, for two minutes, the stem cells were forced into the ventral horn.

At 3:29 p.m., the fifth and final injection began, and two minutes later, the relief was palpable. From her viewing spot just a few yards from Tessaro’s neck, Feldman shifted on her feet and exhaled. The procedure, from start to finish, took a little more than six hours.

Technicians began to check recordings and run over the notes for the FDA. Boulis and the others began the process of removing the device and closing in the gaping hole in Tessaro’s back.

“Can we get some music in here?” Boulis said.

Whiz Khalifa’s rap filled the OR.

Feldman transferred the digital recording of the process to a memory stick she could review back at the office. A copy would go to the FDA, too.

There will be many more months of data, continued animal tests and most likely, hundreds of pages of reports.

Even if this early stage is proved safe and the clinical trial continues, doctors must figure out whether these are the stem cells that work best in this therapy, and, if so, in what amounts and injected into which areas. There’s the issue of the patients’ bodies rejecting these foreign bodies, too.

“This is not a small molecule pill, and your patients go … home and take the pill and you see them in your clinic in a few months,” said Steve Perrin, CEO of ALS Therapy Development Institute, a Massachusetts-based nonprofit focused on finding a treatment or cure for ALS. “These are the challenges this trial and this technology have in front of (them). They’re paving the road, because no one has been down this way before.”

On Friday, Tessaro was recuperating at home.

Waiting for any good news

In the Kleiss’ Royal Oak home these days, Riley the bassett hound has learned that her owner’s lap is no longer hers.

The Kleisses continue to wait for any news they can on ALS — possible cures, treatment, a clinical trial that could involve Regis — “anything,” Mary Kleiss said.

Her son’s voice is gone, so his words are more carefully chosen these days. It’s tedious work: A reflective dot on Regis Kleiss’ forehead strikes the digital keys on a laptop screen in front of him as he twitches and turns his head to manipulate the words. “Y Me” he wrote, in April:

“It sucks to watch my body fai

l.

“While my mind n emotions r completely intact

“Knowing full well the end result

“And the road I’ll be forced to walk

“Becoming a prisoner in my own body

“Watching my world fly by

“Remembering how life used to be

“Missing so much of life.”

More Details: FOR HELP, INFO

• The ALS Association, based in Washington, advocates for ALS patients. Call 202-407-8580 or visit www.alsa.org.

• ALS of Michigan, based in Southfield, offers programs and services for ALS patients and their loved ones. Among the services are loans for medical and other equipment. Call 800-882-5764 or visit www .alsofmichigan.org .

• The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention operates a national registry to collect data from ALS patients to help scientists learn more about the disease. The registry and more information about the disease can be found at www.cdc.gov/als.

• The University of Michigan Health System is in Ann Arbor. Visit www.umich .edu and search for “ALS clinic.”

• The Harry J. Hoenselaar ALS Clinic is at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit. Call 313-916-2835 or visit www.henryford .com/als.

• Mary Free Bed Rehabilitation Hospital is in Grand Rapids. Call 800-528-8989 or visit www .mary freebed.com and search for “ALS.”

COMING MONDAY

Researcher Dr. Eva Feldman campaigns to move ALS trials to U-M